The Huns And Magyars Of The Caucasus

![]()

- Mubariz J. Khalilov ā Szabolcs (Sabolch) Nyitray

āThe only small area that remained extensively under the Huns control in Europe was [following the death of Atilla in 453] the land of the Huns of the Caucasus, from Derbent to north of the shores of the Caspian Sea. According to the Armenian and Arab sources, the Caucasian Huns, later on fell under Khazar rule and, in the 8th century, they were still fighting the advancing Mohammedan Armies from the south.ā[1] These statements are accepted in the circle of historians as viable facts, because they were jotted down by no other than KĆ”roly CzeglĆ©dy, who blindly followed the Finno-Ugric theory of origin.

It is obvious that we must question how, and especially why, the Huns of the Caucasus ādisappearedā from the stage of history, when they were still mentioned as Huns in the great Arab-Khazar war in 722 A.D., in the region of Northeastern Caucasus. A second thought immediately comes to mind; how is it possible, no matter how great a pressure was exerted upon them, that they could all have vanished into thin airā¦?

The Finno-Ugric scholars have failed to give an answer to the most basic question, yet there is

a significant fact[2] from this period in history. Just a few hundred kilometers south of this area, Magyars (Hungarians) lived in the 750s under the name Sevordi/Siyavurdi, who have been identified by historians throughout the world as Savard-Magyars.

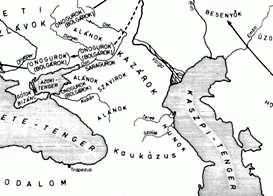

Ā Ā Ā So: what exactly does this mean? According to the entire Hungarian scientific community, in 722 A.D., the Huns were living in the Northeastern Caucasus and, around the same time, about 200 kilometers (!!!) south of todayās Azerbaijan, according to the maps of the Academy of Sciences āafter 700 A.D.ā (!!!) ā and, according to Gyula NĆ©meth and KĆ”roly CzeglĆ©dy from 576 A.D.[3] (!!!) ā there existed the Savard-Magyar homeland; even so, they exclude the possibility that the Magyars have any connection to the Hunsā¦

Taking into account the historical analogies, it should have been obvious that these Magyars might have come from the territory of Dagestan. The situation becomes even more interesting, when we see that, with exception of ĆrpĆ”d Berta,[4] all the other scholars connect the Magyarsā other, original name ā Savard ā to the Savirs/Sabirs, who lived in the same territory, that is, in the Northeastern

and the Southeastern Caucasus, which is the territory of todayās Azerbaijan (see the work of Menandros from 576). GĆ©za FehĆ©r, KornĆ©l Bakay, IstvĆ”n Kiszely, ZoltĆ”n Dolnics, JĆ³zsef BĆrĆ³ and Csaba Z. TĆ³th have stated with authority that, not only was our name Savir/Sabir, but we, Hungarians, are identical to the historical Savirs (lately a lot of people say that); the scholars at the Academy vehemently deny what is self-evident. If we base our investigation on facts, instead of subjective theories, we can state with certainty that there has to be some relationship between the Magyars and the Caucasian Huns and also the Savirs, because there is a great overlapping connection in names,

in territory and in time, which, based on statistics, could hardly be considered accidentalā¦

(Tibor Halasi-Kun came very close to the same conclusion, but it seems, he gave in to the Finno-Ugric censorship.)

Around 948 A.D. Termachu (Arpadās great-grandson) and Bulchu led a delegation to the court of the Byzantine Emperor. The delegation made it known to Constantine Porphyrogennetos that the earlier name of the Hungarians was Savardi, which is, according to the official academic circle, synonymous with the name: Savir/Sabir. Even Gyula NĆ©meth believes that, in the forms from the Greek source, the savardi/savarti/savartĆ¼, the di is only a Hungarian suffix.[5] Therefore, the Hungarian name: Savar/Sabar is exactly the same as the Savir/Sabir form.

It is important to know that in ancient and middle Greek times, or in the Byzantine era, they did not make a distinction between the b and the v. In any case, it is not significant, because the sounds b and v are easily interchangeable.

The accuracy of the note of Constantine VII, in regard to the original Hungarian name: Sabir, is supported by the existence of more than one Hungarian place name. For example: Szabar (in Eng.: Sabar) in āBurgerlandā[6] (first mentioned in 1453 as Zabar); Zalaszabar which was originally Szabar (first mentioned in 1239 as Zobor; in 1335 as Sabaar); in Baranya County, SzĆ©kelyszabar which was Szabar before 1907 (first mentioned in 1389 as Zabar) and in NĆ³grĆ”d County, there is a village named Zabar (first mentioned in 1332 as Zabary). In VeszprĆ©m County, within the boundaries of KĆ”ptalan-tĆ³ti, there is the Sabar vineyard, which is a reminder of the former settlement from the Middle Ages, named Sabar. Moreover, this Sabar form is the oldest form of the Sabir name.[7] We have one Sabar name in the Volga Bulgar region on an epitaph from 1291. The person was the daughter of Burash bey and her full name is Sabar Ilji.[8]

In addition to this, there is a host of other settlement names, which could be mentioned as being connected to the original Savar/Sabar name of the Magyars; such as SzĆ³vĆ”ros (first mentioned in 1507 as Zowaros), HajdĆŗszovĆ”t (f.m. in 1332-37 as Zohad-Zowad), MagyarszovĆ”t (f.m. in 1213 as Zuat), SzĆ³vĆ”rhegy (f.m. in 1469 as Zohanhegh), Szavata (f.m. in 1602 as SzovĆ”ta), RĆ”baszovĆ”t (f.m. in 1224 as Zoac), SzalĆ”rd (f.m. in 1291 as Zalard, cf. Liudprand: Prince Salard [in Hungarian: SzalĆ”rd] from the 10th century.) and also GyerekszovĆ”d and SzovĆ”d Plain in Hont County.

In addition to this, there is a clan named Sovard, which, according to Gyula NĆ©meth and Gyƶrgy Gyƶrffy, is derived from the earlier name of the Magyars: Savard. Gyula NĆ©meth extensively expounds on it, offering as proof four examples that the name of this clan [which is noted by Anonymus, KĆ©zai and the Illuminated Chronicle] and the Savard peopleās name are not only etymologically identical,[9] but their relationship can also be proved historically. According to Anonymus, Zuard Ā [written in the Latin alphabet; which reads in Hungarian: SzovĆ”rd (Eng.: Sovard)][10] waged war in the Balkans, where he also took a wife for himself, >>and the people, who are now called Chabaās Magyars,

after the death of Zuard remained in Greece.<< The history of the Savards has clearly been preserved in the memory of the people, that is the people named Zuard (Savard), (folklore changed it into

a personās name, which often occurred) broke off from the Magyars.[11] (It can almost certainly be stated that the SzĆ©kely Sovat branch is an adaptation of the Savard/Sovard name of the Magyars.)

Gyƶrgy Gyƶrffy is also in agreement with this. He believes that the branch broken off from the Magyars, mentioned by Anonymus, can be identified with a people in the legend of origin of the ancient Gesta. If we take it into account that, in Hungarian legends, every historical event is connected to the name of a certain leader, and the names of peoples are personifiedā¦ it is possible, in fact probable that, according to the 11th century legend of origin, the descendants of Menroth, who migrated to Persia, are known by their leaderās name. The sons of Menroth, the ones who lived in Persia, could not have been other than Zuard. Zuard is also a personified peopleās name, which is the third and the oldest name of the Magyars, according to Constantine. Taking this into account, if we complete that section of the Hun history, which deals with the Savards with the fragment mentioned by Anonymus, we will arrive at the following reconstruction:

>>>ā¦Menrotā¦absque Hunor et Moger plures filios generavitā¦ Zuardu, qui introivit terram Persidemā¦Sui filii mortuo Zuardu in Persia remanseruntā¦et eorum posteritas Persidem inhabitant regionem statura et colore Ungaris similes, tantummodo parum differunt in loquela<<<.

The eleventh century Magyar-Savardian tradition was preserved in such form. That is, the eleventh century tradition (the old Gesta) saved a memory of the part of the Magyars that moved to Persia in ancient times, and their descendants spoke a language similar to that of the Magyars at that time.[12]

In 2008 with less information, we also believed that the Savard name of the Magyars and the similar Savir/Sabir name are one entity, it is just a strong possibility, but nowadays we are certain that they are one and the same. We do have numerous place names in the form of Sabar/Zabar, which is without a doubt the historical name of the Sabirs. Gyula NĆ©methās contention that, in the name Savardi, the di is a suffix must be correct. He brings up several concrete examples in his book. Also, the sounds b and v are twin sounds, and their parallels, to this day, are found in many Hungarian place names.

Then, there is Derbendname (Book of Derbent), which is a reliable and independent source, especially about the land of the Sabirs and the Huns of the Caucasus, that is Dagestan, where we find the cities of Kichi Majar and Ulu Majar, which came into being under the rule of Khosrau I Anushirvan (531-579).[13] (āKichiā is a Hungarian word, it means; little. It is in Turkish; kĆ¼chĆ¼k, in Azeri; kichik, in Kumyk; gichchi [Š³ŠøŃŃŠø]. āUluā means; big in the Turkic languages.) The last time Kichi Majar and Ulu Majar, which had independent rulers, were mentioned ā as allies of the Khazar Khagan ā, was in a collection of sources, which was compiled between the 5th and 11th centuries, in relation to the great Arab-Khazar war of 722.[14] (Kichi- and Ulu Majar have no connection to the city of Kummajar or al-Majar in Stavropol in the 14th century, which has often been proposed in the past.)

|  |

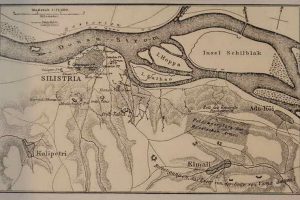

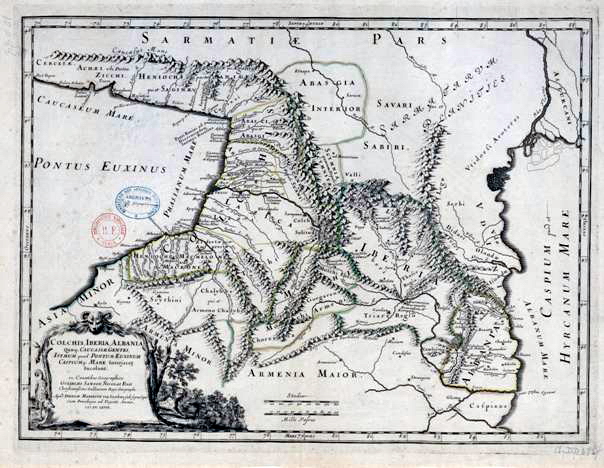

| Armenian map about the region and the KINGDOM of the HUNS with the Terek and Sulak rivers | Terek and Sulak (Szulak) rivers with the Huns (Hunok) in the Caucasus (Bertha 1988, 244.) |

The number of examples weighs more heavily on the side of the truth, than on the side of accidental chance, and they also match up with time and area. Only some of the lesser issues need to be cleared up, in order to see just how and when the Savard-Magyars ended up in the territory of todayās Azerbaijan (Caucasian Albania, then Arran), and also a majority of Magyars in Levedia, and another smaller group in Bashkiria. This is the time (722), when the Huns of the Caucasus finally disappear from written sources, and the Khazar Empire collapses. The result of this is that the political centrum moved, from the area of the River Sulak, some 100-kilometers to the north. (Could there be any connection between the name of the River Sulak, and the name of a Hungarian wild flower, Sulak: convolvulus or morning glory?) The new Khazar capital, Itil, is usually placed on the delta of the River Volga, but there are some who place it more to the north, around todayās Volgograd.[15]

We know exactly when the major cities along the area of the River Sulak fell under Arab conquest, led by Jarrah, and when the conquered people, named Khazars, were moved to Arran in large numbers. It was the failure to connect the Magyar/Majar name to the data of the Savards that caused the break. This void was filled by important information contained in Derbendname; therefore, we can consider it to be the āmissing linkā in the early history of the Hungarians, because there is the connection in area (Dagestan) and in time (6th century to 722 A.D.). It should also be mentioned that the name Magyar/Majar to refer to the Magyars is used all over the world in the Turkic languages, in the Arab, Persian and some Caucasian languages. The name Majar still exists in some of the Hungarian dialects of some regions such as: āÅrvidĆ©k in the county of Vas and the land of the SzĆ©kelys in Transylvania, and also among the CsĆ”ngĆ³s, Majar still being used.ā[16] According to the accepted view of the philologists at the Academy of Sciences āthe ancient j, at the end of that age, was already pronounced as gy [sound closest to dy]ā.[17] For the j<gy development as an analogy just see the evolution of title name jula<gyula and other Hungarian words.[18] Also, according to TESz, āthe time of the change of the sound j>gy (~dy) in the word Magyar could not be more closely determined.ā[19] From this, one can conclude that the name Magyar originally sounded like Majar in the Hungarian language and, therefore, this developed as a ātwo directional sound equalizationā at the same time as, and in parallel with the Megyer-Magyar interchangeable sound.[20]

Many scholars believe that the name of the Hun king, Mogyeri (Mojarı) from 527-528[21] is connected with the word Magyar. This appears to be supported by data in Derbendname, which is a totally independent source of information. In addition to this, the name of this Hun king matches, sound to sound, the āold Mogyeri formā.[22] It is certain that, in the early Magyar language, the sound gy did not exist, just as it does not exist in Turkic languages; even the pronunciation of it is quite difficult for them. It also likely that the sound gy did not exist in the language of the Huns, just as it did not exist in the original Magyar. In the Turkic languages the vowel harmony (synchronization) is quite apparent, which means that any word that does not follow this pattern is mostly not of Turkic origin. In addition to this, even the prefixes are followed by the low and high vowel harmony.

In addition to this, in Greek, the name of a Hun king[23] exists in two variations: Muayeris and Muageris. Following BĆ”lint HĆ³man, Gyula NĆ©meth and Gyƶrgy Gyƶrffy believe that Mogyeri is the proper pronunciation, while DezsÅ DĆ¼mmerth insists on Magor.[24] The Mojar(ı)-Mojgar(ı), or Majar-Majgar pronunciation is more likely. The āıā in the Turkic languages is similar to the Hungarian āiā, but itās a low sounding vowel, like the Russian Ńı (yery) ā, which is pronounced āiā in the Greek and Hungarian, but in actuality this is not important, because the Greek names generally end with is,

so the Moj(g)ar/Maj(g)ar is very possible. Gyƶrgy Gyƶrffy writes: āIt is widely believed that the name Muageris is the first appearance of the Magyar peopleās name, but this has yet to be proven.ā[25] He adds: āIn this personal name many see the Magyar peopleās name, and suggest that it is relevant to the Hungarian people.ā[26] (Compare with Tibor Halasi-Kun.)[27] This was written by one of the most renowned members of the Academy and an expert in Hungarian ancient history. We believe that

we have sufficiently presented our case, based on the independent sources and the data from Derbendname, about the (KICHI) MAJAR of the 6th century.

In 1913, near Hasavyurt, there still existed a geographical name āMaŹgarā and a village name āMaŹgar-yurtā.[28] (The Ź is pronounced like in the French jeton, Jean or measure, intrusion in the English.) (yurt is a Turkic word, meaning: homeland, land, shelter, home.) These place names were written down in Russian in the 19th century, at the time when the Russian language did not have the letter or the sound j, so they used the Ź instead. The combination of the d and Ź (d-Ź)> j came into use during the Soviet era. Today that region is occupied by the Kumyks, but their Kipchak language also lacks the sound j, so they simply pronounce it Ź. It is quite possible that the pronunciation of Majgar and Majgar-yurt sounded pretty much as we know it in the Hungarian, and as Ibn Rusta wrote down as Majgar in the early 10th century. It is not as if a half-sound would make much difference, but to see the word Majgar, side by side in Derbendname and Arab sources, looking exactly the same, is very convincing. The discovery that these place names still existed at the beginning of the 20th century, could be considered to have significant historical value, because it underscores the findings of the earlier researchers who were on the right track, pointing out that the Magyars lived in the Northeastern Caucasus. However, from here on, the Savard-Magyar issue becomes really interesting.

|  |

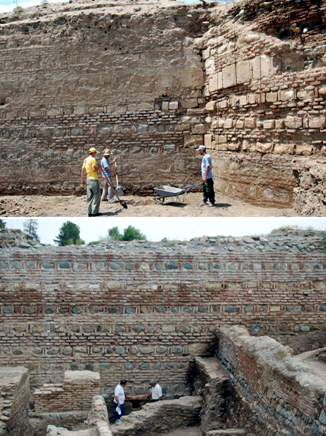

| The ruins of Shemkir | |

The 9th and 10th century Arab sources (Baladhuri, Masudi) mention a Siyavurdi/Siyavardi ethnic group, which, around 752, captured a city named Shemkir (Shamkhor or Shamkur) in Azerbaijan, and they destroyed it completely.[29] (The later cityās impressive brick and stone walls have survived to this day and, even in ruins, they are very imposing.)

The Siyavurdi tribes, mentioned by the Arab historians, are believed to be the same as the Sevordi ethnic group found in the Armenian sources from the Middle Ages.[30] The Byzantine Emperor, Constantine Porphyrogennetos (913-959), in his work: De Administrando Imperio (the Governing of the Empire), calls the Magyars Savardi-AsfalĆ¼ (asfalĆ¼ or asfali means āunshakableā). The Sevordi people were first identified with the Savardi by Ya. K. Grot in 1881. Following this, numerous inter-national and Hungarian historians accepted his statement (for example: JĆ³zsef Thury, Gyula NĆ©meth, Gyƶrgy Gyƶrffy, KĆ”roly CzeglĆ©dy, Gyula KristĆ³, Vladimir Minorsky and Mihail Artamonov). Based on written information by Constantine VII, in Levedia (most common opinion that from the Azov-sea to the River Kuban), after the Kangar-Pecheneg attack on the Magyars ā called Turks ā the Magyar Army split into two. One part of them moved to the east and settled in Persia, and they became known as Turks (Magyars) and, to this day, they are called Sabartoi Asphaloi,[31] by their former name.[32] Most historians believe that this happened significantly later than the occupation of Shemkir in 752, as was recorded in the previously mentioned Arab sources. Formerly, everyone accepted 889, the date given by Regino, the Abbot of PrĆ¼m, as the date of the first war between the Magyars and the Pechenegs. This seems to be supported by the statement of Constantine VII, that the first Pecheneg assault came in Levedia, and it was followed by numerous events within a short period of time, such as the meeting between the Khazar Khagan and Levedi, and later on, the election of Arpad. A few years later,[33] the Pechenegs attacked the Magyars a second time. We can state that this surely happened in 895, if we insert the conquest of the Carpathian Basin, into the greater historical picture.

First of all, we have 889 as the date of the Pecheneg attack, recorded by Regino, the Abbot of PrĆ¼m (he does not mention a second attack). Secondly, there is the conquest of 895, which was preceded by the Pecheneg assault, according to Constantine. Between 889 and 895, the difference is only āa few yearsā, but Regino referred to all the events, connected to the Magyars as taking place in 889,[34]

so he mentions only one Pecheneg attack, unlike Constantine. Gyƶrgy Gyƶrffy challenges the accuracy of the date 889, set by Regino as the first Pecheneg assault, and also the migration from Levedia into āEtelkƶzā (that name is only a possible reconstruction), todayās south region of Ukraine.[35] (According to KĆ”lmĆ”n SzƶllÅsy, Levedia is the region of River Kuma and Etelkƶz is between the Rivers Volga and Don. In the Gesta of Anonymous Dentu-moger [Dentű-mogyer[36]] means DontÅ-magyar, because we have seven Hungarian place names[37] by backwater or creek with tÅ or tű suffix in estuary meaning. Furthermore den means river in Alan language.[38])

About thirty years ago, most researchers of Hungarian ancient history began to look for an earlier date regarding the migration from Levedia to Etelkƶz. We believe that this is significant because, according to Constantine, this is the time when part of the Magyars migrated to Persia, which is identified by all historians as a land southeast of the Caucasus.[39] The time frame for this migration

was estimated to be from the 830s to the formerly generally accepted date of 889. For example: JĆ”nos Harmatta: 830, LorĆ”nd BenkÅ: 860, and so on.[40] Based on our present knowledge, this issue could not be solved satisfactorily. The second problem is that most historians do not agree on the date of the migration from Levedia. Gyƶrgy Gyƶrffy sets the first Pecheneg attack in the 750s, the same time as the migration of the smaller Magyar group to Persia.[41] This matches the notes of Baladhuri (Baladzuri), who stated that the Siyavurdis appeared in Azerbaijan, and in 752 looted Shemkir; if so, this contradicts Constantineās time and place, because it occurred 150 years earlier, somewhere in the bend of the River Volga, and not in Levedia.[42]

Theoretically, we could accept the date and place given by Constantine regarding the consecutive Pecheneg assaults, as well as the fact that part of the Magyars purposefully migrated toward the southeast beyond the Caucasus Mountain range, in the ā approximate ā direction in which their relatives had moved some 150 years earlier, so that they could join them and live in security.

In addition to Gyƶrgy Gyƶrffy, KĆ”roly CzeglĆ©dy and DezsÅ DĆ¼mmerth also declared that the Pecheneg attack took place some 200 years earlier than Constantine recorded, reasoning that, in the collective memory of man, the events of the past are compressed.[43] Later on Czegledy re-evaluated his previous view regarding the migration of the āSavarti Asfali into the Caucasus redating it to 854, when the two great passes through the Caucasus Mountains were secured for their passage. This migration was caused by the battle between the Kangar-Pecheneg and the Savard-Magyars.ā[44]

In any case, if M. I. Artamonov and Gyƶrgy Gyƶrffy blame Constantine VII for confusing the time and place of the first Pecheneg attack and the migration of the Savard-Magyars into Persia, there is the possibility of a second wave of Magyars in the 9th century to the Southern Caucasus, which is quite acceptable (The first one was noted by Baladhuri). āBaladhuriās information shouldnāt be rejected outright; therefore, the appearance of the Savards in Armenia (actually in Albania-Arran)[45] can be determined to be between 750 and 760.ā[46]

Lately, some researchers pose a serious problem with the contention that there never was a āfirst Pecheneg attackā, because the Pechenegs first crossed the River Volga in 894, as a result of the Uz (kind of Oguz) attack upon them.[47] At this time, the Magyars had lived by the shores of the Black Sea for at least 150 years. So, these two peoples could not have confronted each other in Levedia or farther east. There are no explanations for why part of the Magyars, keeping their earlier Savard name, migrated āafter 700 A.D.ā from Levedia to the Southern Caucasus, a theory which is accepted by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.[48] There seems to be a gross contradiction, which to this day has not been solved.

Therefore, on the territory of todayās Azerbaijan, regarding the historical events of the 8th century, the mentioned Sevordis could be connected to the Magyar colony in Dagestan in the 6th to the 8th centuries Kichi Majar and Ulu Majar. The geographical closeness and the historical connections (between Huns of the Caucasus, Sabirs, Khazars and Albania-Arran) could offer a logical explanation and solution. It should be mentioned that generations of historians have āblamedā Constantine for confusing the time and place: Yes, the break up of the Magyars could have happened, but not northeast at the bend of the Volga; instead, southeast on the territory of Alania-Dagestan (part of the Magyars migrated to the Southern Caucasus), and not as a result of the Pecheneg, but rather the Arab assault. A good 200 years later, Constantine could have made a mistake about this tooā¦

The tenth century Armenian historian, John Katholikos of Drashanakert (Yovhannes Drasxanakertcāi), in regard to the events of the ninth century, writes about the history of Uti province near the city of Shemkir ā also known as the country of the Utis ā where Sevordis lived too; so one could theorize that there is some connection between the Utis and Sevordis.[49] (Some believe that the people named Udi, are actually the descendants of the Utis. Their number is less than 10 thousand. They have preserved their ancient Caucasian language and Christian religion. Most of them live in the villages of Oktenberi [in Georgia], Oguz and Nij [in Azerbaijan].) Baladhuri, in the 9th century, wrote that Shemkir was flooded by Siyavurdis from all directions.[50] This indicates that the Siyavurdis may have settled in great numbers on a large area.

The famed tenth century Arab historian, Masudi, places the Siyavurdis on the shores and valley of the River KĆ¼r (Kur or Kura) near Tiflis (Tbilisi). He writes of them as powerful and battle-tested people and, at the same time, he says, ethnically they are Armenians.[51] (al-Istakhri writes of them similarly in The Book of Roads and Empires, in a later insertion: āBehind Barda and Shamkur there are the Siyavardis of Armenian extraction, a useless, rotten and pillaging people.ā[52]) The statement by Masudi, in regard to the Sevordis being Armenian, could be based on two observations. The first one is people-etymology.

The name Sevordi is a distorted form of the original and correct Savarād-i people name in the Armenian language. The sev means black, the ordi means boy in the Armenian language. So, the original Savardi (sav-ardi) became sev-ordi, meaning āblack boysā (switching two vowels). Savardi is very close to Sevordi in pronunciation, but they have no etymological connection. It was also stated by Gyula NĆ©meth: āIn the Hungarian word Savardi, the di is a Hungarian suffixā¦ The Savardi form appears in the work of Constantine Porphyrogennetos and Baladhuri in the 9th century. The Savardi form could be explained by the etymylogy of the Armenian language, meaning āblack boysā. The Persian word siyah, meaning black, explains the Siyavardi in the Arab sources. The Armenian Sevordi found its way into the Greek language too. Constantine, in his work De caerimoniis mentions the Savards as Ī£ĪµĻĪ²ĪæĻĪ¹[įæ¶Ī½] [=Ī£ĪµĪ²ĪæĻĻĪ¹-] (serboti [seborti]), and he translates their name as: ĪĪ±įæ¦ĻĪ± ĻĪ±Ī¹Ī“ĪÆĪ± āblack boysāā¦The name of this people in Magyar was Savardi, from which came the Armenian form, Sevordi, āblack boysā, a folk etymological switch.ā[53]

Contrary to Masudi, the Armenian historians do not consider the Sevordis (Savards) as Armenians. In a number of sources, they write that the Sevordis pillaged their land and rejected Armenian authority. They helped the Arabs and Turks to conquer and occupy Armenian lands.

JĆ³zsef Thury (1861-1906), a philologist and turkologist, researched this subject extensively,

and he was the first to collect important source material. His priceless pioneering work deserves a direct quotation, in his own words, from his work of 1897: āWhen the rulers of the Dynasty of Pakraduni began to govern in Armenia, the Sevordis often attacked the territories of Armenia from the province of Udi, pillaging and causing a lot of destruction. Because of this, in 886, Ashod I (859-890) led an army against the people who lived in the Kukar and Udi provinces, and also in the passes of the Caucasus Mountains. He defeated them and that ended the looting. He also made them accept him as their ruler, and appointed governors over them. But within two years, in 888, they revolted against the oppression, and Ashod put together an army of Armenian and Georgian soldiers, and put his eldest son, Sempad (or Sembat), in charge. He was victorious in a number of battles, and in Armeniaās northern part (the historical Albania-Arran Uti province, inhabited by the Sevordis) he stayed behind as vice-roy until his father died in 890. Then he appointed governors over the Sevordis and moved

to take over the throne. Under his rule, the Sevordis in the province of Udi revolted again, but Sempadās luck must have held out, because Patriarch Yohn, in his work, writes that Sempad was able to expand his conquest along the River Kur all the way to Tiflis, in the province of Udi, and he advanced to the cities of Hunaragerd (Hunarakert or, in the Arab source, Hunan), Dus (city of the Sevordis) and Shamkhor. But the Sevordis did not accept him as their king; they preferred to fight

on the side of the Arabs. In 909, Yusif, Governor of Azerbaijan from 901, led an army against Armenia and ravaged a significant portion of it. The following year, Sempad sent his own armies against Yusif, and put his two sons, Ashod and Musheg, in charge of a division of Sevordis, who were now fighting on his side. Sempadās armies met the Arab armies beside Jegnavadsar (province of Nik) [the western side of Lake Sevan/Gƶyche, northeast of Yerevan] near River Hurasdan [today: Razdan]. [In reality, ethnically they were probably completely mixed. Muslims of local Albanian ancestry, Arabs, Iranians and Turk soldiers composed Yusifās army. The conversion of Arran to Islam began in the second half of the 7th century and ended at the end of the 9th century. Yusif himself, while a nominal member of the Central Asian origin Saj clan, was a ruler of Azerbaijan independent from the Caliphate.] The two enemy armies attacked each other with great ferocity, resulting in the defeat of the Armenians, because the residents of the province of Udi and the army of the Sevordis, in the heat of the battle, switched over to the Arab side. One of the two leaders, Ashod, was able to escape, but Musheg was captured and he was taken to the city of Tovin.ā[54]

Later on, Yusif of the Saj (Yusuf ibn Abiāl-Saj) captured the Armenian King, Sempad, and in 914, hanged him in the city of Dvin, then conquered all of Armenia. This is an account recorded by the Armenians, which means that the Sevordis were not Armenians. In spite of being Christian, on the battlefield, they betrayed the Christian Armenians and joined forces with the Muslim so-called Arabs.

In the 10th century, Masudi mentions a battle-axe that was named after the Siyavurdis (Savard-Magyars), which was the special weapon of the Siyavurdi tribe (tribes). Later on, āother barbarian armiesā used it, but it kept its siyavurdi name (Muruj ez-zeheb ve meāadin el-jevahir, XVII, Ā§31).

The reality is that we donāt know much of the life and history of the Magyars migrating across

the Caucasus Mountains and settling in Azerbaijan. We should take into account that only

some of the sources survived; others have perished in the ravages of time, but there still might be some, which give an account of the āunshakableā Savards and the feared Christian Kingdom of the Transcaucasus region. All we know definitely about the land of the Sevordis is that it was located in the valley of the River KĆ¼r (Kur-a), ābehind Barda and Shamkurā and the western border was not far from Tiflis; so, one can draw a reasonably accurate borderline on the map. It is not a large area, but it existed, and the contemporary Armenian and Arab sources give reasonable information on its history. āMasudi mentions that he wrote the history of the Sevordi people. This work, sorry to say, to this day is unknown. He talks believably about the work named Akhbar-ez-zeman, which he mentions a lot, but so far only the first volume was found in Aleppo in 1849.ā[55]

Constantine VII mentions the ancient name Savarti when writing about the Magyars, because this is the name they used themselves.[56] āBack in those times, they werenāt called Turks [the Greek name for the Magyars], but for some reason Sabartoi Asphaloi (Savarti Asfali)ā¦ Some of them settled east,

in the territory of Persia and, up to this day, they are called by their old name Sabartoi Asphaloi.ā[57]

All of this was written by Constantine around 950, and he took the information from Bulchu and Termachu, when they were in a delegation to the Court of the Byzantine Emperor. (Termachu; he was the great-grandson of Arpad; Bulchu received the honorary title of āFriend of the Byzantine Emperorā from Constantine VII.) IstvĆ”n ErdĆ©lyi, under the penname āIstvĆ”n Petrikā, called attention to the similarity of the name of āPrince Termachuā, the son of Teveli and the great-grandson of Arpad and the name of āa military leader, Tarmach, who is possibly the son of the Khazar Khagan, and was in charge of the army in 727 that defeated the Arabs in Azerbaijan.ā [Artamonov 1962, 211. 48. j., according to Gevond].[58] Interestingly enough we know one more Khazar name Buluchan,[59] that is very similar to the Hungarian Bulchu. In addition to the information given by Termachu and Bulchu to the Byzantine Emperor, the reports of other delegates must have been valuable to the Emperor.[60] Since the authenticity of the information given by the Emperor is not disputed by any serious historian, we can be sure that the name Savarti is the one the Magyars used for themselves, and was not one attached to them by others (such as āTurkā by the Byzantines). Furthermore, it is supported by the second national name: Savard, which is the original name and found in written sources.

One interesting thing is about the Hungarian name of Kursan (He was the co-prince of Arpad as a kende [or kĆ¼ndĆ¼] and died in 904). That name appears as a hun superior; Zirdkin-Khursan in the compiled chronicle (7th-10th centuries) by Albano-Armenian historian(s) Moisey of Kalankatuk (Moses Kalankatvatsi).[61] The same name, Khursan also appears in some sources from the 6th century as a fortress or province between Derbent and Shirvan.[62] Later on regarding the Arab expansion the name of Khursan emerges again by Baladhuri and Yaqubi in the 9th century. Baladhuri says about the suzerainty of Lakz/Legz (Lezgin) shah, who is called Khursan and the territory situated on the boundary of Masqat (Massagetae). Masudi in 943 mentions that Muhammad ibn Yazid shirvanshah captured the ancient principality of Khursan. Look at this topic in more detail by Minorsky.[63] The azerbaijani historians say that the armenian Yeghishe (410-475) wrote earlier the Khursan name in History of Vardan and the Armenian War.[64]

The early Magyars of the Caucasus were also known to foreign geographers; Lajos Tardy discovered the secret 16th century map, which is kept in the National Library of Vienna, on which Georgia is located, between the Black Sea and the Caspian-Sea (that is all of the Northern and Southern Caucasus), and called the former land of the Magyars. The original handwritten Latin text is as follows: Georgia seu Hungaria antiqua, which means: āGeorgia, the former Hungary.ā[65] This was marked in such a way that āGeorgiaā represented the whole of the Caucasus and was identical to the former homeland of the Magyars in Dagestan. It should be mentioned here, āaccording to an old Chechen legend, two of their tribes migrated with the Magyars from Asia to the Caucasus, and they consider us their relatives.ā[66] Stephanos Orbeli archbishop of Sunik (Zengezur), in 1287, mentions an etymologically disputed place name in the donation letter of a vineyard, which āhappens to be on the land of the Sevordis.ā[67] This place name was Madsharaga/Macharaka-yor (Valley of Macharaka), in which the -ka/ga syllable, according to Thury, could be an assimilated Armenian plural, therefore it may mean the Valley of Magyars. It is certain that the Armenian language does not have the sound j; therefore, they have substituted it with ch in the word Magyar/Majar (Machar). At the same time, Gyula NĆ©meth believes that the Armenian place name stands for the Valley of Cheese, which seems pretty far-fetched, to say the least, if we take into consideration the general rule of place name selection. It is most likely that Madsharaga/Macharaka means; Majar-aga, because in the 13th century ā and even before that ā the Turkic word aga (aka) was well-known and extensively used in the Armenian language. It means Sir, leader, boss; so āMagyar-aga valleyā appears to be most likely. In the 13th century, an Albano-Armenian historian, Kirakos, lived in the city of Ganja (or Genje). In his Armenian language work, History, the word āaga/akaā appears in the names of leaders, like this: Tonguz-aga (chapter 29), Sadek-aga (chapter 39), Tora-aga (chapter 57). In addition to this, Kirakos, in chapter 32 states that āagaā, among the Mongols means ābrotherā. āWe do not know any other Mongolian words, but we do know this oneā, remarks the author.

LĆ”szlĆ³ Bendefy wrote the following: āThe Sevortis of the region of Kur, the 11th century geographical name of the land of the Savards, could refer to none other than the Savard-Magyars, who fled to the vicinity of the River Kur, and settled in the province of Udi.ā[68] Regarding the āassimilationā of the Savard-Magyars, there are different theories: According to Gyƶrgy Gyƶrffy, the Papal Bull, issued by Pope John XXII in 1329, along with the Alans and the Malkaitas, mentions Prince Yeretan (or Yeretamir) of the Magyars in Asia ā which is the last mention of the Savard-Magyars. Others think that these people were those, who were dragged away by the Mongolians in 1241, and settled in todayās Stavropol at the confluence of the Rivers Kuma and Buyvola (See the city of Kummajar or al-Majar in the 14th century). Everyone agrees that, at the ābeginning of the second millenniumā the district of the Sevordis was still in existance.[69]

The expression Savardi (black-boy) in the etymology of the Armenian people became widespread in the Middle Ages among the neighbors of the Savards (Utis, Armenians, Albanians, Alans, etc).[70]

In the territory of Azerbaijan the village name, Majar Garaoghlan (in Azeri: Macar QaraoÄlan,[71] that is Magyar Black-boy), in the 19th (and 20th) century, could be led back to the people-etymology for sure (in the Azerbaidjani language, gara-oghlan means black-boy. The primary meaning of oÄlan [oghlan] is boy, and the secondary is child). The use of the names Majar and black-boy at the same time strongly support each other, therefore, we can state that our contention is proven, in regard to village names. In addition to the village of Majar Garaoghlan, in the 19th century, there existed a settlement named Majarlı (Macarlı),[72] meaning: from the Magyar Clan, or belong to the Magyar Clan. āMagyariā is an old expression, but it could be translated to āmagyarosā also, which means: typically Hungarian. The village of Majarlı does not exist anymore, and the geographical location could not be determined. Two villages with the name Garaoghlan remained on the left bank of the River KĆ¼r (or Kura). One of them is in the county of Aghdash (AÄdaÅ), the other one in the county of Yevlakh (Yevlax), in that area, where the province of Uti used to be and where the Savard-Magyars settled. They are mentioned in the works of Istakri also, like wild thieves. They lived north of the imaginary line between Barda and Shamkur. The Arab source uses the word ābehindā, looking north from Baghdad, where the two villages of Magyar origin still exist even today.

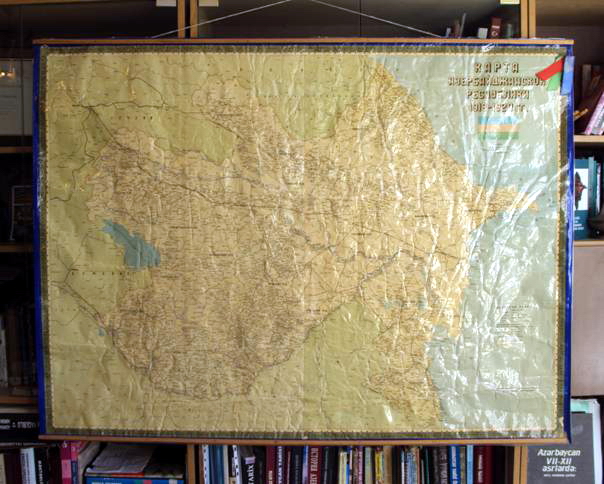

On a detailed map of Azerbaijan as a Democratic Republic, reprinted in the 1920s (which was a copy of a map made during the rule of the Czars in the Russian Empire), in todayās county of Yevlakh, the village of Garaoghlan appears as Majar Garaoghlan.[73] The disappearance of the word Majar is probably due to the Soviet anti-Hungarian sentiments during the World War II. The people-etymological name Sevordi (black-boy) in Armenian was probably widely known and spread in the Late Middle Ages among the Azerbaijanis, and this is why they used the two words (Savard-Magyar) in combination, although originally they had the same meaning: Majar.

This village name proves that the ancient Magyars, at that time ā and this is supported by Constantine Porphyrogennetos ā had two names. Moreover, the Magyars called themselves by these two names; Majar and Savard at the very same time, so these two names referred to the same people. This does not necessarily mean the ethnogenesis of two ethnically different peoples that blended into one. It is certain that both the Savard and Magyar names refer to the Magyars, as Constantine noted over a thousand years ago.

In addition to these villages, settled by Magyars (their direct descendants still live there), in the county of Nakhchivan (Nahichevan) Sherur, beside the settlement of Dasharakh, there is, to this day, a territory named Majar-yeri, that is Magyar-place.[74]

This is far from the territory settled by Savard-Magyars. Nakhchivan is not even connected to Azerbaijan proper by land, because it is an enclave, a wedge of land, between Iran and Armenia, some 13 km. south, where the Rivers Araks and Arpa (the word āarpa/Ć”rpaā has the same meaning in Turkic languages and Hungarian) flow together, in the eastern Valley of Ararat. There is no known direct connection to this Hungarian place name, but there is an interesting note by Gyƶrffy: āRubruk, on his return journey in 1253, in the city of Naxua [Azerbaijani: Nakhchivan, Russian: Nahichevan], which lies beside Araks, met a Hungarian Dominican, who was going – from Tebriz – to Tiflis.ā[75] (W. Rubruk: XXXVIII:5) Gyƶrgy Gyƶrffy supposes that this Dominican missionary from the Carpathian Basin might have met the Savard-Magyars, because he must have known of them; although Rubruk makes no mention of them, this supposition cannot be excluded.

In connection with the Sevordis, that is the Magyars of Azerbaijan, there is another outstanding piece of information: Abdul Fida names part of the Khazars ā Garajur.[76] This people probably migrated to Azerbaijan between the 7th and 9th centuries, from the Northern Caucasus. In Karabah (Garabagh) in Azerbaijan, in the 19th century, there still existed the Garachor tribe, who were the direct descendants of the Garajurs as the Arabs called them. Within their population, at that time, there still existed a Clan named Garavurd.

The name of the Garavurd Clan is the same as the Armenian Sevordi, and the Persian-Arab Siyavurdi: sev/siyah/gara, which, in the languages of the Armenians, Persians and Azerbaijani-Turks meant: black. The vurd, the second part of the word gara-vurd goes back to the Persian-Arab word ā Sijavurdi [siya(h)-vurdi], which is derived directly from the Armenian Sevordi. This, in turn, is the Armenian version of the original Magyar name ā Savard. Therefore, we can safely say that Savard was the original form, from which all the other variations are derived.

In Azerbaijan, besides the written sources and place names, there are some examples of material nature too, which indicate the Hungarian connections: Guba is an excellent example; in the counties

of Khachmaz (on the border of Derbent) and Lenkoran, the people used the four-wheeled carriage named: majar-(araba). The majar carriages, drawn by oxen, buffalos or horses, were different from other carriages, because they were longer and higher.[77] The appearance and the spread of the Hun-garian carriage in Azerbaijan are attributed to the ancient Magyars.

The rulers of Kichi Majar and Ulu Majar, who are mentioned in Derbendname, were subordinate to the ruler of Ihran (found in todayās Avaristan), one of the ancient provinces of Dagestan. Moreover, Kichi Majar and Ulu Majar were located in the province of Gulbakh (!), which bordered the province of Ihran.[78] It is also worth mentioning that āthe people of Dagestan, in their own language, called themselves: Maarulal (people of the mountains); others called them: Avar, which is the corrupted form of āAuharā in the Russian language. Others believe the name is of Kumyk (KumĆ¼k) origin, and it means a restless, quarrelling man. There are no known links between them and the Avars of the Carpathian Basin. Some 270 thousand of them speak a different tongue, which is one of the Avar-Andi languages [it belongs in the Dagestan branch of the Caucasian language-family]. Their countryās name, in the Middle Ages (9th and 10th centuries) was Serir, and that was the name of their ruler too. It is possible that Serir was established by the remnants of the Huns.ā[79] The fact is that all the sources and other information regarding the Magyars (Savards) point in one direction, in the direction of the 6th century Kichi Majar and Ulu Majar, as was stated in Derbendname, and also in the note of Baladhuri, regarding the destruction of Shemkir in 752 by the Siyavurdis (Magyars).

Without exception, all major Hungarian historians (Gyula NĆ©meth, Gyƶrgy Gyƶrffy, KĆ”roly CzeglĆ©dy, Gyula KristĆ³ and so on.) ā based on the research of JĆ³zsef Thury ā accepted and acknowledged that the homeland of the Savard-Magyars was in the province of Uti (!), which was bordered on the north by Dagestan and the Northeastern Caucasus! Evidently, this suggests that the āfirstā wave of Magyars (it is uncertain whether or not there was a second one) came from Dagestan, and not from Levedia, which is 800 km distant, or Magna Hungaria (Bashkiria), which is 1500 km. distant as the crow flies.

|  | |

Hungarian style female boots in Azerbaijan | Traditional homespun from Azerbaijan | |

The presence of the Huns and the Sabirs in Dagestan is well-known, and if we add to this, that the presence of the Magyars can be supported by reliable sources, then the key questions in the discussion will be answered, and all the uncertainty deliberately created by the anti-Hungarian scientific com-munity, will be dissolved by this revelation. It becomes obvious just why the Magyars are known as Huns, in all of the foreign and domestic sources, as well as in the memory of the people, and why Arpadās people kept Atilla in their memory as their great ancestor. Why did the ārealā Huns of the Caucasus and the Sabirs (Savirs) disappear from the territory of Dagestan, where reliable sources mentioned them last (The Sabirs were mentioned, under the name sab.r, as one of the first peoples

in the Khazar Empire, established in 650.[80]), and right after that, the Magyars were known as Huns? Prior to this, why was it that the Sabirs (it is virtually certain that Sabirs and Magyars are one and the same people), like the Magyars after them, were known by contemporary historians as Huns?

The second century Claudius Ptolemy indicates the Sauar people (Ī£Ī±į½»Ī±ĻĪæĪ¹) in the European part of Sarmatia. (Geography III:5, Ā§10)[81] That Sauar name near to the Caucasus could mean the Savar-Sabir people very easily.

The Sabirs appeared for the first time in the foothills of the Caucasus in 515 and, after 558, they were not mentioned again ā with the exception of 576, but by this time they were on the other side of the Caucasus (!) and, according to NĆ©meth and CzeglĆ©dy, they may not even have been Sabirs at that time, but rather Savard-Magyars.[82] (?!) ā Gyula NĆ©meth notes, that this is the time (558) when the āSabirs disappearedā.[83] From this point on, one can find references in the historical sources

only to Khazars and Huns (of course, previous to that, there were references to Huns).

In reality, the question is no longer a question, because this whole issue is brighter than the Sunā¦ Because, in the 6th century, the Huns, who were living in Dagestan and on the adjacent plains, blended with the Savirs, who migrated there in 515 and the Magyars (Savardis>Sevordis), who were also living there in the 6th century. It is very likely that the Savirs and Savards are one and the same people. (Everything matches up, the place ā Dagestan; the time ā the 6th century and the name ā Savard or Savir, the former name of the Magyars.)

The Khazar Empire was organized and established around 650, under the leadership of the Sabirs ā together with the Turks ā, and in the beginning, the āyoungā Hun succession state successfully repelled the attacks of the Arabs. In this case, behind the exchange of the name, there could be a power switch within the Empire, in favor of another people or tribe, but the people that constituted the basic building block remained in place. This is why we used the word āyoungā to describe it.

The strength and viability of the Khazar Khaganate was proof that it was capable of blocking the powerful Arab expansion for over a half of a century, a feat of which only a few countries were capable.

The balance of power in this area and time could not exist forever, so, after a comparatively peaceful period, in the beginning of the 700s the hostility between the Khazar Empire and the Baghdad Caliphate was renewed, and it became an expanding and dragged out war. Therefore, the area north of Derbent, in the divide between the Caucasus Mountain range and the Caspian-Sea, the narrow land strip of Middle and North Dagestan ā including the region of Eastern Caucasus ā became a permanent battlefield. According to the Muslim Calendar, in the 104th year of Hijra [722/723 A.D.], under the leadership of Jarrah, the Arabs conquered Balanjar, the Khazarian capital city. Their first attempt in 652 had failed. This is the territory where the Magyars lived. Kichi Majar and Ulu Majar in Dagestan, as noted in Derbendname, was identical to the settlement of Indiri (Endrey), on the bank of the River Sulak, according to Bakikhanov.[84] The city of Balanjar was also in the āvicinity of River Sulakā, like the Khazarsā other big city, Semender.[85] (Some believe that beside the settlement of Upper Chir-yurt, the discovered big city walls and cemeteries could be Balanjar from the 7th century, while others believe that the city of Semender was located in the neighborhood of Mahachkala, where its ruins were found next to the settlement of Tarki ā formerly Targu.) Independent of the above, the place names of MaŹgar and MaŹgar-yurt were found beside Hasavyurt. In addition, there are archeological proofs in support of this. Two kilometers north of the settlement of Endrey-aul ā earlier name Indiri ā ,[86] the Soviet archeologists discovered the foundations of a city. According to the science of archeology, this city was built in the 2nd and 3rd centuries, and it was depopulated[87] during the 8th and 9th centuries, at the time of the Arab-Khazar War.

Far south, in the city of Ardabil, the war went on for decades. According to Arab sources,

the main Khazar Army numbered about 300 thousand, strong in the battle that took place by the Savalan Mountain in 731, and the Khazars annihilated the main Arab Army, massacred all the men and dragged the women and children into slavery. The leader of the Arabs, Jarrah, was also killed. Eventually, under the leadership of Marwan the Arab Army gained the upper hand, and crushed the Khazars and forced the Khagan and his Empire into submission.

According to the Arab sources, Marwan settled the Khazar prisoners onto the plain between the Rivers Samur and Sabiran, south of Derbent, in the territory of Lakz.[88] The 8th century contemporary Armenian historian, Gevond Vardapet, calls the Khazar fortress and the surrounding city, conquered by Marwan, Varachan, which was the āancientā capital of the Huns. He calls the Khazar Empire the āCountry of the Huns.ā[89] Evidently he is in agreement with all the other contemporary Armenian, Albanian and Persian historians, who write of Huns and Khazars living north of Derbent and never of Savards or Sabirs. (These last two are known from the Byzantine sources.)

The name Khazar itself became prominent after the Hunsā power waned, and should be considered only as a collective name, under which there were people not even known by name. This is true even in the center of the Empire, which is noted in Masudiās work, as well as in the works of other Arab historians. It is not clear to many historians just who the Khazars really were. Some believe they could have been any people from the Sabirs to the Turks, even the Kasars of Ancient Uyghuria (nowadays Mongolia). Masudi remarks that the āKhazars, in the Turkic language, are called Sabirs; in Persian, they are called Khazars.ā[90] Earlier, Marquart, Tomaschek and Gyula NĆ©meth also represented this belief. NĆ©meth went on to say that the words, Sabir and Khazar have the same meaning.[91] But, lately, this surmise has been strictly confined by the theory of Kasar-Khazar identity. There is one problem with the Kasars; no source about their migration from Central Asia to the vicinity of the Caucasus, yet some historians accept this idea. With the Derbendname and the āMaŹgarā place names, we can prove that the Magyars also took part in the establishment of the Khazar Khaganate, therefore they them-selves were Khazars. Henceforth, this is not just a theory, but a proven fact, supported by historical sources, official maps and geographical works.

In reality, the only issue that needs to be clarified is whether ā in a narrower sense ā the Magyars (Savards) were the same people as the Savirs? Could it be that Gyula NĆ©meth is correct, when he writes: āThe Savirs of Menandros [the 6th century historian āalsoā mentioned them along with the Alans on the territory of todayās Azerbaijan, at the time when they met the Byzantine Army by the River Kur, in around 574 and 576] could be Savards, but he is talking of Savirs and not Savards. It is also true that the Savards got their name from the Sabirs (Savirs).ā[92] So, if the two names ā Savir and Savard ā are in reality two names for one people (which is supported by the place names ā Sabar/Zabar), then the Magyars received the name, Savir, because they were actually Savirs. We can prove that the Magyars of Dagestan and Azerbaijan lived in the same place as the Savirs, and at the same time. If NĆ©methās contention is factual, then the names Savir and Savard are etymologically the same ā according to him this is certain[93] ā, then in reality, we are talking of the same people, and not of the Magyars in the āFinno-Ugricā fairytale, with a tagged-on alien name, and for some unexplainable reason the Hungarians themselves still believe it. Furthermore, the Magyars (Savards) appear where the Savirs do, in different sources, in Dagestan and by the River Kur(a)ā¦

Let us shed a little more light on this: NĆ©meth says that the names, Savir and Savard, used for the Magyars are the same, but that the Savirs have no historical connection with the Magyars.

Then he contradicts himself. He brings up the possibility that in 576 (!!!), in the valley of the Kur,

the Sabirs were Savards, in reality Magyars! This is unbelievable. We originally would not even dare to go as far as to say that the Sabirs in 576, by the River Kur, were actually Magyars. What is even more fantastic is that he suggests the possibility that, in 576 (!), Magyars may have lived that far south in the 6th century; whereas, based on Derbendname, they lived significantly north of there at that time. If we accept NĆ©methās contention regarding Kummajar, some 600 km. from the River Kur ā where Kichi and Ulu Majar were locatedā¦, then one might ask, just why would the group of Magyars come from Magna Hungaria ā note: before 600 A.D. ā some 1500 km. to the south? This is no less than a gross contradiction.

Just to be sure that we did not misunderstand the words of NĆ©meth, he continues in this fashion: āThere are two hundred years between Menandrosā remarks and the first written information,

during which time there was no mention of the Savards [he is speaking of the same Savards>Siyavurdis that were mentioned by Baladhuri in 752, who lived beside the River Kur ā āinterestingly enoughā they were the neighbors of the Alans (!!!) ā, and everyone considered them to be pure Magyars, including Gyula NĆ©meth], which is most exceptional for such warriorsā¦ā[94]

What is so āexceptionalā to NĆ©meth, is obvious to all the historians of Azerbaijan and Armenia.

The Albanian and Armenian historians called all the horsemen of the Eastern Caucasus, including the āreal Hunsā, collectively Huns ā such as the Bulgars, Barsils, Alans, Haylandurs, Akatzirs, Banjars, Balanjars, Suvars/Savirs, Massagetaens, Khazars, Turks etc. They did not differenciate among them. It made no difference to them, which of the horsemen pillaged their villages; they suffered just the same. They could not determine any real difference among them, because the war they waged toward the south was fought in an alliance. It is not even clear just who the ārealā Khazars were (the same could be said of the Burtases too); moreover, the Massagetaens in Albania and other horsemen,

who moved in from the north and settled there, were called Huns.

This is the case in the works of Gevond, Moisey of Kalankatuk (in Armenian: Moses Kalankatvatsi)[95] or the 5th century Armenian historian, Faustus of Byzantium (Pavstos Byuzand), who states that the Massagetae king, Sanesan, was the commanding officer of the Hun Army (History of Armenia, III:7).[96]

The explanation is quite simple, although NĆ©meth makes it seem incomprehensible, and it is so much more understandable than the Finno-Ugric theory of origin, which cannot be proven with written sources or archeological finds.

Ā

Some believe that the first Hun groups migrated from Asia to Europe, and also into the territory of the Caucasus as early as in the 2nd century. There is some information about this in the works of Dionysius Periegetes (ounni) from the 2nd century and also in Claudius Ptolemy (in the form of hounoi).

The Huns first appeared in Transcaucasia around 225 A.D. In the 5th century, Agathangelos mentions them in his book entitled: History of Armenia. Actually, the historian Movses Khorenatsi, also from the 5th century, mentions the appearance of the Khazars and Barsils a decade earlier, in 215, in the Southern Caucasus, in the Chronicle of the same name. Yusif Jafarov suggests that the Khazars and Barsils were actually Huns, and he is probably right. The Massagetaens migrated quite early, around 270-280, from the Northern Caucasus to Albania, and settled beside the Caspian Sea in the province of Chol.

This whole Khazar, or as the historians called it: Hun state formation ā which was the confederation of a number of different but related peoples ā was destroyed by the Arab attacks in Dagestan,

which caused the ethnic map of the Eastern Caucasus to be redrawn. The Huns were forced to move their capital city āat the beginning of the 8th centuryā,[97] from Dagestan, some 400 (!) kilometers north to the delta of the River Volga, that is to Itil in the vicinity of todayās Astrakhan. This actually became āthe capital city of the Khazars in 729ā.[98] This is a historical fact, which nobody denies.

Because of the expanded and merciless Arab-Khazar War ā in which, according to Derbendname, the Magyars took part and became the victims, since their homeland was a battlefield for decades ā, the smaller part of the Magyars (Savards) united with the Huns and, in the first part of the 8th century, they moved to the southeast and settled in the province of Uti, which was outside the hotbed of the Arab-Khazar War. (This is supported by the information of Baladhuri in 752, that the Siyavurdis [Magyars] looted Shemkir. Independent of Baladhuri, according to Derbendname, the history of Kichi Majar and Ulu Majar in Dagestan, along with their rulers, ended after 722, because of the Arab-Khazar War. The difference between 722 and 752 is right one generation.)

On this point, there are outstanding parallels in different sources, which all support each other.

The Arab sources established that, in 722-723, after Jarrah, the leader of the Caliph, conquered the cities of Hamzi[99] (Hamlij), then Targu,[100] and eventually the fortress of Balanjar,[101] the capital city of the Khazar Empire, he deported the inhabitants to the vicinity of Kabala (Gebele) in the province of Uti, and that is how the Khazar villages were established[102] in Azerbaijan (on the territory of Arran). (That these strategic mass deportations and settlements were the practice of the Caliphate is shown by the deportation in 735, during the Kazar campaigns in the territory of the Volga, of some 40 thousand Khazar and Burtas prisoners,[103] who were also settled in Arran, that is in todayās Azerbaijan.)

It is known that Balanjar, the flourishing capital city, was located in the vicinity of River Sulak in the first part of the 8th century.[104] We also know from Derbendname that the history of Kichi Majar and Ulu Majar, and the history of their rulers, ended right after the Khazar defeat in 723.

Bakikhanov also informs us that Kichi Majar used to lie on the banks of the River Sulak (if by any chance he is mistaken, it can be stated for certain, based on Derbendname, that the two Magyar cities were located in the Northeastern Caucasus). In 1913 the village of MaŹgar-yurt still existed at the locale in question. There was also a geographical name: āMaŹgarā identified at that time.

This is supported by the fact that Derbendname makes a last note of the location of the two Magyar cities in 722, at the time of the Arab-Khazar War, which matches in time and in territory the Arab occupation of the area of the River Sulak in central Khazaria in 722-723, including the fall of the capital city of Balanjar. In addition to this, in 723, Jarrah conquered Alania, which was the central province of the Khazar Khaganate.

On this point, the different sources support each other as far as time and place are concerned.

Yet, from other totally independent sources, we also learn that Magyar settlements (Hungarian villages still exist in the counties of Aghdash and Yevlakh), existed only 20-30 kilometers southwest of the city of Kabala (also the county of Aghdash bordering the county of Gebele in the northeast).

To be exact, the city of Aghdash is exactly 45 kilometers from the city of Gebele (Kabala),

and the Hungarian villages are not far from there. Keep in mind that the former Magyar settlements extended far beyond the three villages (Majar Garaoghlan, Garaoghlan and Majarlı). One might say that some of the Khazar villages overlapped the Savard-Magyar villages, and vice-versa. āAt worstā, they must have been close neighbors. Besides this, the place of their origin is the same: along the River Sulak in Dagestan.

All of this is of enormous importance, because it could not be a coincidence that all of the sources support each other in time, place and description of the final destination, which is the area of the

River Sulak, and then, in 723, the province of Uti!Ā Everything points to the theory that, from the vicinity of the three Khazarian cities, the Savard-Magyars were deported and then settled in the province of Uti in Arran. It should be noted that the Magyars were one of the major ethnic components of the Khazar Empire, because they were located in the central part of the Khaganate where the largest and oldest cities were located near the capital city, Balanjar, along the River Sulak. Semender was located here also, in which, according to Istakhri and Ibn Haukal, in the 10th century the Christian Church was still standing.[105] According to the account of the Arab geographer, al-Maqdisi (al-Muqaddasi), some of the residents were still Christians.[106] Many Huns of the Caucasus were converted to Christianity by Armenian and Albanian missionaries in the 6th-7th centuries.

Zacharias Rhetor, the Syrian historian of the 6th century, states that Kardost, the Albanian bishop, translated the Bible into the language of the Huns. Since the Albanians hoped that the conversion of the Huns to Christianity would stop them from pillaging their country, after Kardost had served

14 years in Dagestan, Varaz-Tradat, the Albanian king, with the help of the Albanian Catholicos of Yelizar, reorganized the mission in 681. They sent Bishop Israil from Barda to the land of the Huns beyond Derbent (Kalankatuk: History of Albania, II:39).

We know from the Albano-Armenian historian, Moisey of Kalankatuk that, when Bishop Israil crossed the Iron Gate of Derbent and arrived in the country of the Huns in 862 (History of Albania, II:39), they worshiped the god, Kuar, who was capable of delivering lightning strikes, and if anyone was struck down and died, they offered an animal sacrifice to their god in order to conciliate him (II:40).

The godās name, Kuar, is an interesting name, because in todayās Slovakia (which used to be a part of Hungary) by the River Ipoly, there is a settlement named KĆ³vĆ”r. In 1257, it was called Kuar.[107]

This underscores the correctness of the Albanian account, in regard to the name of the Hun-Sabir god. Furthermore, the name of the Alan leader, who migrated to Gaul (todayās France) in the 5th century, was Guar, and in the new homeland, the descendants of the Alans also used this name.[108] Since we know that the Alans were neighbors of the Sabirs and Huns (by the time of Bishop Israil they were more like Hunsabirs) in the Caucasus ā north and south ā, the parallel is inescapable. Beside SzĆ©kelyudvarhely (in Transylvania), the natives call the Mountain Range opposite Mount BudvĆ”r āKovarā. That is interesting, because this territory is supposed to be the area where the SzĆ©kelys used to offer sacrifices in a pagan ritual, before the Magyar settlement of the Carpathian Basin.[109]

The Hun ruler, Alp Ilitver (Alp Elteber), influenced by Bishop Israil, adopted Christianity, together with his people (II:41). The Albanian bishop, in his report of 682, mentions that āChristian Churches were built in the country of the Hunsā ā even before him ā, and the city of Varachan (II:39), the headquarters of the Hun King, Alp Ilitver, was āmagnificentā.Ā There were streets and squares in the city, where skillful carpenters worked, who respected Aspandiat as a saint, and considered her the mother of the giant oak trees, out of which they carved a huge cross decorated with tulips[110] and other motifs. Earlier, the Hun-Sabirs used to go to these sacred oaks ā trees of life ā to offer their sacrifices, which they sprayed with the blood of a horse, and then they hung the skull and hide of the horse on the tree (II:40-41). KornĆ©l Bakay pointed this out ā rightfully ā as a partial horse-burial.[111] Let us see what IstvĆ”n ErdĆ©lyi writes about this: āā¦mainly the menās, but some womenās graves contain the hide of the horse and the bones of the legs and the skull, placed there after the mourners had consumed the meat of the horse.ā[112] In most of the Turk graves, the complete skeleton of a horse can be found, which was the accepted custom of the Turks.

It should be considered very significant that the Bishop saw Varachan as āmagnificentā, because he came from a country ā Albania ā, in which, well ahead of Northwestern Europe, there were huge cities with stone and brick buildings with sewer and water systems. (Many believe that the fortification discovered in the 1960s in Urtzeki in Dagestan used to be the city of Varachan.)

The conversion of the Huns of the Caucasus is significant, if we accept that, at that time, in the province of Uti, the Savard-Magyars were already Christians, so much so, that one of their leaders, Stephannos Kon, became a martyr of the Christian Church.

JĆ³zsef Thury researched the works of the Armenian priest and historian, Mikayel Chamichyan (1738-1823). According to Chamichyan, when the Turk governor of Armenia, Bugha the Great (Bugha al-Kabir/al-Turki), launched a Transcaucasia campaign from the city of Tovin, in 854,

and in the province of Uti, destroyed the Sevordisā city of Tus (or Dus) the leader of the Sevordis, Stephannos Kon, was captured. (Prior to this, Bugha had captured the Uti leader and defender of the stronghold of Karich.) Following this, he continued his conquest through Alania, all the way to Tiflis. After the successful campaign, in the following year, 855, Bugha the Turk marched the Alan, Armenian, Uti, Albanian and Sevordi (Magyar) prisoners of war in front of the Caliph of Baghdad.

In the Palace of Baghdad, the Caliph gave them a choice: renounce Christianity and convert to Islam or be tortured to death. Among the faithful ones, who chose the latter, was Stephannos Kon,

the leader of the Sevordis, whose bravery was exceptional.[113] Those who stood by him were the Princes George and Arwes, who were brothers, and who became saints of the āArmenian Churchā, although they were Sevordis (see footnote 45.). This proves that the Sevordis were Christians in the first half of the 9th century. Gyƶrgy Gyƶrffy writes that the Savards āin 854 were Christians and most likely influenced by the Armenians.ā[114] If we consider that, in Derbendname, beside Hasavyurt,

there are two places called MaŹgar, then we might think that, even before the Magyars migrated to the province of Uti, they could have converted to Christianity in the territory of Dagestan, a part of the Hun Kingdom, where they were influenced by Armenian and Albanian missionaries. It is known from sources of Armenian language that the Armenian and Albanian missionaries succeeded in converting some of the Huns of Dagestan ā perhaps many of them ā to Christianity. This did not mean that,

all of a sudden, they gave up their old traditions and beliefs completely. It was most likely that the old and the new religion existed side by side for some time.

In the case of the Magyars, Prince Geza (972-997) supported a stable central government based on Christian principles. His son, Saint Ishtvan (997-1038) joined the Church of Rome, and embarked on the āChristianizationā of his people. Many more scholars are taking it upon themselves to study the āpaganismā of the Magyars before Saint Ishtvan, because it is interpreted in different ways, while the Hungarian Chronicles are heavily influenced by the Roman Church and Western European views. From IstvĆ”n BaĆ”n to KornĆ©l Bakay, scholars have established that, in Hungary, before the conversion of Saint Ishtvan, there was a strong Byzantine Christian influence.

Therefore it is quite possible that the roots of Christianity stretched all the way to the Caucasus and its seeds were sown in Albania and Armenia. The Hungarian crosses worn in the 9th and 10th centuries support this viewpoint. They are quite individual and without parallel. Christ is not depicted crucified on them, but with outstretched hands.

This information in itself should make one realize that, within the Caliphate of Baghdad in 854, there were Christians (!) ā a fact, which is accepted by everyone from Gyula NĆ©meth to Gyƶrgy Gyƶrffy[115] ā, yet we are told that, in the Carpathian Basin, surrounded by Christians on all sides,

the early Hungarians, even in the 11th century, vehemently clung to their supposed āpaganismā. Be-hind this, there must have been something other than what is generally accepted. Perhaps it was not that they were non-Christian but that they were āprovincialā (according to GĆ”bor Pap), or as Bakay says, the arrival of the powerful Magyars in 895 signaled the beginning of the ethnically and nationally charged east-west struggle and these clashes, later on, were characterized as anti-Christian, which is being held responsible as the major cause for that conflict even today.

According to tradition, Hungarians are the descendants of Nimrod. JĆ³zsef Thury, who has extensively researched the Armenian sources, which write about the Sevordis, stumbled on an amazing information. This becomes particularly important, since we have proved that the Sevordis were really Magyars. Let us not forget that, even the members of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences have accepted this, which in itself is no small thing. Let us quote JĆ³zsef Thury who, to his surprise, discovered this coincidence in regard to the belief of the Magyars of the Carpathian Basin: āI should mention the exceptional statement by the first Armenian writer, Patriarch John, who wrote about the Savartis, who says that the Savartis in Armenia were the descendants of Kush, who was the son of Nimrod.ā[116]

Evidently this legend existed even before the Magyars came to the Carpathian Basin, and it was not a creation of the Arpad Dynasty, nor did it originate in the Hungarian Kingdom or in Western Europe. It must go back to the time before the Magyars separated into two groups, and before 752, when Baladhuri first mentions the Sevordis in the province of Uti. Therefore, it was not the creation of the Roman Churchās clergy either. It suggests some Christian and Biblical connection though, because these two names, āNimrodā and āKushā also appear in the Old Testament and in the Syrian traditions. Consequently, the Hungarians were not āpagansā after all. (There are even problems with the exact meaning of the Latin word.)

There are other sources supporting the information that the Magyars were one of the major components of the Khazar Khaganate: āAccording to 10th century sources, such as the works of Constantine Porphyrogennetos and Bruno of Querfurt, the Magyars were at that time bilingual. Emperor Constantine made his notes based on the information given to him by the Magyar leader, Bulchu. One of the two languages was of Turkic kind…ā (DĆ¼mmerth)[117] āDuring the time of Arpad and his sons, the earlier leaders of the Seven Magyar Tribesā¦ negotiated in Turkic in Constantinople. Denis Sinor points out correctly, in his presentation given at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences on the occasion of the 200th birthday of Csoma SĆ”ndor KÅrƶsi, that the Emperor or the writer of the chronicle could have made a mistake, but it is not likely that the interpreter made a mistake about the language he was interpreting from.ā[118] Among the Magyars, it was customary, to speak a second language (Turkic), besides the mother tongue, because it was necessary in the multi-national Khazar Empire, especially since they lived in the center of the Empire. If they had lived on the fringes,

or near to the border, they would not have needed, nor would they have had the opportunity to learn the second language on a wide scale. According to NĆ©meth, āWe must treat this issue very carefully, because we should not presume a direct language connection between the Khazars and Magyars.ā[119] Question: If this is so, why were the Hungarians bilingual on a wide scale?

Interestingly enough, at one time, Gyula NƩmeth taught the same as KornƩl Bakay, IstvƔn Kiszely and others that the Magyars represented a major power in the center of the Khazar Khaganate,

before the Arabs expelled them. This is the only possible explanation for why the Hungarians were speaking two languages, at least for two generations after they had settled in the Carpathian Basin. Gyula NĆ©meth writes: āAccording to Ibn Fadlan, the language of the Khazars is different from the Turkic and the Persian language, and it does not resemble any other languages. Istakhari and

Ibn Haukal repeated this statement, but the latter writer adds a significant note to it: āthe language of the REAL KHAZARS is different from the Turkic and the Persian language.ā It is not clear who the ārealā Khazars were, as noted by Ibn Haukal but it is clear that there were many languages in the Khazar Empire. Ibn Haukal knew that the language of some of the Khazars had no connection either to the Turkic or the Persian, not even to any other language. In addition to this, Istakhri and Ibn Haukal state: āThe language of the Bulgars is like the language of the Khazars.ā This contradicts Ibn Fadlanās contention, that: it does not resemble any other languages. Therefore, the notes of Istakhri and Ibn Haukal are contradictary, but independent of each other.ā[120]

Many believe that the Arab sources refer to a single Khazar language, yet even Gyula NĆ©meth,

who is anything but āpartialā to Hungarian issues, points out that there are at least two different Khazar languages. Those researchers, who evaluate the sources with a lax attitude (by simply neglecting important information) and summarize their conclusion in an equally lax manner,

such as in the Lexicon entitled: A vilĆ”g nyelvei (The Languages of the World), published in the year 2000, ignore the mention of the āreal Khazarsā in the Arab source. If there were āreal Khazarsā, then there must have been ānon-real Khazarsā: the lesser Khazars, who spoke a different language and these were those, whom the Arabs differentiated from each other on account of their language.

We can conclude the following: There were at least two Khazar languages; one for the āreal Khazarsā, and another for the ālesser Khazarsā, just as in Belgium there are two languages: French and Flemish. It is rather strange, that the authors who published their books with the Academy Publishing Co. never came to this conclusion. Tibor Halasi-Kun wrote in 1943: āWe may conclude from the Islamic sources, although they sometimes give conflicting information, that, in the Khazar Empire, there were many languages, and even the Khazars themselves spoke more than one language.ā[121]

Later on NĆ©meth continues in this way: āAfter all, the note of the geographer Muqaddasi is quite interesting: āThe language of al-Khazar is very ambiguous.ā These sources tell us that in the Khazar Empire, people spoke a language, which was different from any other known language. (Here we cannot help but think of the Hungarian language).ā[122] This was written by none other than Gyula NĆ©meth and, in this, he does not differ from the opinion of KornĆ©l Bakay: āIs it not our language (Hungarian), which has not the least resemblance to any Indo-European or Slavic languages? According to Masudi, the Persians used the name Khazar for these people, and the Turks called the same people Sabirs. This is very important (for Hungarians), because it supports Emperor Constantineās note, regarding our early Savard<Sabir name.ā[123] The Byzantine sources differentiated the Magyars from the Khazars by calling them Western-Turks and Eastern-Turks. We can add to this more than ten place names like KazĆ”r, KozĆ”r, KozĆ”rd, KozĆ”rom, etc.[124]

Besides the mentioned Arab sources that pointed out the unusual language of the āreal-Khazarsā (See Halasi-Kun, who quotes several researchers),[125] there is al-Maqdisi, who notes that, in the 10th century, when the Magyars (he calls them Turks, as most do) waged war against Andalus,

several of them were captured, but no-one understood their language.[126] Just as there are no ārealā Belgian or Swiss people, there were no ārealā Khazar people either, because under this name,

in reality, they included the Magyars. Derbendname proved with the Majar place names that,

in the Khazar Khaganate, the Magyars were the determining major component. That had to be the reason why, in his letter, Khagan Josef used the Hungarian word: āĆrā (Lord) to refer to the king.[127]

The Khazar as a political name is widely used by foreigners, in a general sense (just see in the Derbendname), yet the word itself might originate from the name of an Uyghur or Turk tribe: kasar/gasar. It is significant that the name Khazar first appeared at the time of Khosrau I Anushirvan, who founded Kichi- and Ulu Majar in the Northeastern Caucasus, and none other than Gyula NĆ©meth himself calls attention to this.[128]